Thank goodness for Tonya Harding. If it weren't for her trailer trash ass, the American public would never have rejuvenated its interest in figure skating. But while most of us can sit on our couches and appreciate the grace, athleticism, and froofy costumes of figure skaters, few of us understand exactly how the sport works. How do the judges come up with their scores? What makes one jump tougher than the other? Calm yourself, gentle reader. In this SYW, we'll not only supply you with a little history about figure skating, but we'll also teach you how the sport works, so that you too will froth at the mouth, waiting to see whether that Uzbekistanian waif will beat the Russian favorite (again).

1. KNOW THE HISTORY

You're probably just reading this SYW so you can impress all of your friends with your knowledge about the difference between a Lutz and a Salchow. But before we get to the good stuff, you need to brush up on your figure skating history.

School Figures

No, we're not talking about 2s and 4s (nor about the shapely cheerleader in the back row). Figure skating gets its name from the Compulsory Figures (also known as School Figures) skaters did in competition up until 1990. When a skater competed in Compulsory Figures, he/she would trace a set pattern on the ice, such as the ever-popular Figure 8. To make matters more difficult, the skater had to skate the Figure using a prescribed part of the blade (such as the forward inside edge of the left skate, but more on that later). After the Figure was completed, judges would get off their fat butts and squat down on the ice to check the tracing and see how close it came to perfection. They took points off if the tracings didn't match the set pattern (if the skater went too far before turning, for example) and if there were additional tracings caused by putting the other foot down or wobbling. As you could probably imagine, Compulsory Figures did not exactly make for compelling television, and they were eliminated in 1990.

Why was the School Figures competition ever a part of figure skating? Because it rewarded skaters for technical perfection much more accurately than current judging methods do. It is often said that "old school" pre-1990 skaters had much better edge control than today's skaters (who spend all their time practicing jumps), while today's skaters can have messier technique but still win competitions.

Professionals vs. Amateurs

The labels for skaters have changed over the years. In the good old days we had Amateurs and Professionals. It was easy to tell them apart: Professionals got paid and Amateurs did not. Amateurs competed in the Olympics while the Pros wore feathers and skated in the Ice Capades.

Times have changed. Due to the huge expense of the sport (it can cost a good skater over $40,000 per year just to prepare to compete in standard competitions), skating federations have given these kids a break. Amateurs are now allowed to earn money, but-and here's the catch-only from sanctioned events. So, what does this mean? First of all, it means that the old categories are obsolete. Now skaters are called Eligible or Ineligible. Eligible skaters are those who are still eligible to compete at the Olympics while Ineligibles have given up that right by competing in an unsanctioned event.

OK, so what is an "unsanctioned" event and who decides whether a skater can participate? Questions, questions! This is how it works: each country is governed by a skating federation (entities like "Congress" and "the House of Lords" are just figureheads). For example, the United Skates Figure Skating Association (USFSA) is the American governing body. One job of that federation is to determine which events allow skaters to maintain their eligibility. Once an event has received the blessing of the USFSA (and we are talking shows, tours, and competitions here) all skaters are free to participate.

So, why would anyone want to give up his or her eligibility? Wouldn't doing so be moronic? Nah, there are actually three good reasons why skaters choose to give up their eligibility:

- If skaters have already achieved Olympic success and don't feel the need to continue the grind of serious competition, they can decide to "retire." This means that they are no longer interested in serious competition but still want to skate on tours and in shows (think Tara Lipinski, who retired at the age of 17 after winning big gold at the 1998 Olympics).

- If skaters have had run-ins with their national federations, they might want to turn ineligible just to gain some freedom (think Surya Bonaly, who was so anxious to get out from under the constraints that the French federation had put on her, that she did an illegal move at the 1998 Olympics to break away).

- Skaters often decide to give up their eligibility if they have been competing for years and have never made it to the Olympics or any other major competition. These skaters typically join tours such as Holiday on Ice or Disney on Ice (think of about a thousand skaters that you have probably never heard of because they never made it on TV).

2. LEARN ABOUT THE BASIC STRUCTURE OF A PROGRAM

Figure skating takes just as much athleticism as (if not more than) hockey, but it throws in the added requirement that the athleticism must look effortless. Now that Figures are out of the mix, skaters are left with two phases of competition:

- Short Program (a.k.a. Technical Program) - it lasts about 2 ½ minutes

- Long Program (a.k.a. Freeskate) - it lasts 4 minutes

The short program, usually worth about one-third of the overall score, consists of a group of required elements that the skater can execute in any order to the music of his/her choice. At the elite level (the level shown on TV just about every weekend throughout the winter), the men and women have three jump requirements, three spin requirements, and two footwork requirements. Failure to execute any one of these requirements results in mandatory deductions in score. To add to the stress, skaters are not allowed to retry a botched jump in the short program; once it is done, it is done. The short program is considered a nerve-wracking do-or-die situation, since one missed element can drop a skater out of contention for a medal.

The long program, typically worth about two-thirds of the overall score, provides a bit more flexibility. There are no set requirements, although most of the top women today include 6 or 7 triple jumps, several spins, and even some triple-triple combinations. Most competitive men do the same, and recently have been attempting quadruple jumps in their Freeskates. You'll learn more about this terminology later. All that you need to know now is that the top echelon of skaters will try to stuff as many tough jumps as possible into their long programs so they can earn brownie points.

After each program, a skater receives two sets of scores:

- The Technical Mark (also called the First Mark) is for required elements (in the Short Program) or technical merit (in the Long Program). It reflects the difficulty of the program as well as the clean execution of all the spins, footwork, and jumps.

- The Presentation Mark (also known as the Second Mark) reflects the choreography, flow, and balance of the program. It is also a measure of the skaters' ability to interpret their chosen music, make good use of the ice surface, and skate with speed, sureness, and effortless carriage.

These scores range from 0.0 to 6.0. 6.0s are extremely rare (even Olympic gold medallists rarely get 6.0s), so you'll more often see scores ranging from 4.8 to 5.8 for the top skaters. It is important to remember that while some of these aspects are subjective (such as judging how well a skater interprets his/her music), there still are specific guidelines. For instance, a properly executed jump means that the skater takes off on the correct edge, and a properly executed spin means that the skater maintains the correct form throughout the spin.

By the way, if all of this jargon is getting confusing, don't worry - it will soon be so clear to you that your friends will weep with envy. Okay, maybe not, but it will still be cool for you to know.

3. LEARN ABOUT THE JUMPS

Many people who watch figure skating on TV simply see a skater fling himself/herself into the air, twist a couple times, and land backwards on one skate. But all the jumps look kinda the same . . . what makes one jump more difficult than another? Glad you asked, because we've already written out the answers.

In figure skating, there are two basic kinds of jumps:

- Toe Jump - this is when the skater uses the toe pick (the tiptoe of the skate) of one skate to vault up in the air

- Edge Jumps - this is when the skater takes off from a specific edge of a skate without the benefit of help from the other skate. A toe pick push-off isn't allowed.

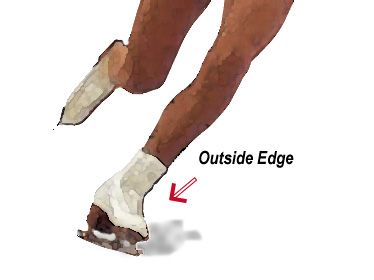

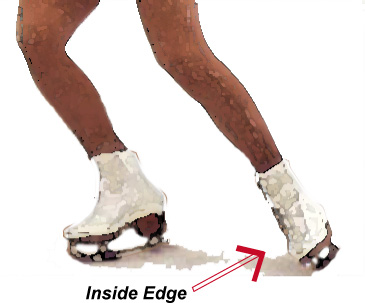

When talking about edges, skaters get very specific, saying things like "left back outside edge." In order to understand the edge terminology, you just need to break that statement down. "Left" refers to the foot . . . so there can be right and left edges. "Back" refers to the part of the blade near the heel, while a "Forward" edge is the part near the toe. "Outside" refers to the side of the blade facing away from the other leg. We hope that "Inside" would then be self-explanatory.

The skaters you see on television all have about six jumps in their repertoires - Toe Loop, Flip, Lutz, Salchow (pronounced "sow-cow"), Loop, and Axel. A single, double, triple or quadruple jump refers to how many times the skater spins in the air between the takeoff and landing. Finally, these jumps can be done in combinations, meaning that two jumps are done right in a row, without any extra steps taken in between.

Toe Jumps

Toe Loop The easiest toe jump is called the Toe Loop. To perform a Toe Loop, the skater glides backward on the outside edge of the right skate, jabs the left toe pick into the ice, and then rotates to the left. Because this jump is so easy (just jab the toe pick into the ice and jump), it is often done as the second half of a combination. The second-easiest toe jump is called the Flip. The Flip looks a whole lot like the Toe Loop; the only difference is that the skater glides backward on the inside edge of the left skate and toe picks with the right foot to start the leftward rotation. One hint about spotting a Flip is the entrance. Most skaters start by gliding forward in a straight line on the left foot with the arms out and the right leg up in front. The right leg then taps the ice as the skater rotates ½ a turn to the left so that he/she is traveling backward. The right leg is still elevated, which is good because it is needed to hit the ice to start the rotation. Now on to the Lutz ... Being able to identify the entrance to a jump is perhaps most helpful with the Lutz because it is so similar to the Flip. Like the Flip, the Lutz uses the right toe pick to vault the skater off of his left leg. The difference is that the Lutz uses the left outside edge instead of the inside. This slight shift of weight makes this jump much more difficult and in fact, one way to cheat the Lutz is to switch to an inside edge at the last second (this is called a Flutz, since it is really a Flip disguised as a Lutz). The entrance of the Lutz is what makes it easy to identify. Skaters typically do their Lutzes in the corner of the rink after taking a long glide on a curving diagonal to set up the proper edge.Edge Jumps

Salchow The Salchow is named after Ulrich Salchow, a skater from the early 1900s. This jump takes off from the left back inside edge. Typically, the skater turns counterclockwise on the ice, standing on the left leg, settles into that left back inside edge, and then scoops the right leg up and over the left to initiate the jump rotation. Being able to swing the right leg around to gather momentum helps to make this the easiest of the edge jumps. The Loop (not to be confused with the Toe Loop) is one of the most difficult jumps, edge or toe, because the right thigh has to do all the work without any help from a toe pick or a swinging free leg. In this jump, the skater starts by skating backwards on two feet, with the left foot crossed in front of the right. Then, the skater simply (yeah right) springs off of the right back outside edge, keeping the feet crossed, and rotates to the left. The Axel is probably the most identifiable of all of the jumps because it is the only one with a forward takeoff. In all of the other jumps, the skater both starts and ends gliding backwards but the Axel takes off from the left front outside edge. Since it ends backward like all the others, a triple Axel is actually 3 ½ rotations, making it more difficult than the other triples.The only jumps Eligible skaters intentionally do as doubles are the Axel and the Toe Loop, or Loop if it comes as the second half of a combination. Otherwise, all jumps are supposed to be triples or quads. If you see a skater perform a double Lutz, for example, you know that he or she has just made a big mistake and the First Mark (the technical score) will take a hit.

Oh, one more thing: when the skaters spin in midair during a jump, they can turn clockwise or counterclockwise. Most skaters rotate counterclockwise (which is a trait of right-handedness), so that's how we described everything above. If you are dying to know how a clockwise skater might go about one of these moves, simply change the words "right" and "left" and you'll be all set. Either that or take it up with your local chapter of Left-handed Elitists For Triumph (L.E.F.T.).

Now, you can read about the Jumps all day long. But to truly learn the jumps, you need to watch a professional and then practice on the ice. check out these figure skating videos on ehow.com. You can learn how to do almost anything by watching the videos on ExpertVillage.

Illustrations proivided by Julie Yu Chin Liu and are 2000, SoYouWanna.net, Inc.

4. LEARN ABOUT THE SPINS

There are tons of spins out there, and new ones are being invented every day. The most important things to keep in mind when watching any spin, though, are: speed, number of rotations, center, and control.

- Speed and number of rotations go together since faster spinners can get more revolutions during the same period of time. Getting in as many revolutions as possible is important in the Short Program, where there are requirements and deductions will be taken if you don't meet them. Also, fast spins with several rotations show mastery and skill.

- Centering a spin is the ability to rotate several times in the same spot on the ice. If a spin isn't centered, it will "travel," which is kind of like a top wobbling across a table as it slows down. Being able to have a good center is a sign that you are a masterful skater.

- Just as important as how fast you spin is your level of control (how you look doing it and how you look coming out of it). Flailing or sloppy arms, for example, are a no no since they show the judges that you aren't balanced. Similarly, a beautiful spin is marred by a wobbly exit, so it is important to maintain control throughout.

Scratch Spin

One popular type of spin is the Scratch Spin (also known as a Blur Spin, a Corkscrew Spin, or an Upright Spin). In this move, the skater stands up straight with the legs crossed. Arms are either held overhead or in front of the body while the skater turns. These spins are always crowd pleasers so they are often used as the ending move in a program. Check out this video of Paul Wylie performing a Scratch Spin.

Camel Spin

Another common spin is the Camel Spin, in which the skater stands on a straight leg with the other leg and torso in a parallel line to the ice. There are several variations on the Camel, including the Flying Camel (in which the skater jumps before settling into the spin), a Hamill Camel (in which the Camel Spin turns into a Sit Spin, named for Dorothy Hamill), and a Catch Foot Camel (in which the skater arches her back to grab the blade of the free leg-it is also called the Donut Spin since the body ends up in an O shape). Watch this video of Maria Butyrskaya doing a couple of standard Camel Spins.

Sit Spin

During a Sit Spin, the skater bends one leg while extending the other out in front. The lower the bent standing leg, the deeper the sit, which results in a better all around spin. Here's a video of Todd Eldredge doing a couple of Sit Spins.

Layback Spin

A common spin done mostly by women is the Layback. In this position, the body is leaning either backward or sideways while the free leg is bent diagonally toward the back. Here is a video of the ever-popular Dorothy Hamill executing a classic Layback Spin.

As we said, new spin positions are being invented all the time. Just in the last few years we have seen the advent of the Pancake Spin and the Martini Spin. While these sound delicious, they are not as famous as the Biellmann Spin, which is named after the Swiss former World Champion Denise Biellmann. In this spin, again, mostly done by women, the skater arches her back and pulls her free leg high over her head. Comfy. Here's a video of Denise Biellmann doing her spin.

5. LEARN ABOUT THE DIFFERENT COMPETITIONS

OK, so you are now a figure skating mavin. You know about the jumps, the spins, the structure of a competition, and even a little history. But here's the biggest mystery: which one of those Sunday afternoon broadcasts should you watch?First off, there are two whole sets of competitions that never make it to television but are incredibly interesting:

- Non-qualifying competitions, also called Club Competitions. These competitions happen throughout the year at rinks all over the country. They are called "non-qualifying" because winning one doesn't make you eligible to skate in another. It's a competition completely unto itself. Non-qualifying competitions bring in both little children experiencing their first competition and high-level athletes who wish to try out a new program without the pressure of an ABC Sports camera following their every move. Typically, these competitions cost about $5 to watch in person, and are a great place to learn more about the grassroots side of the sport.

- Qualifying competitions such as Regionals and Sectionals. At these events, skaters at all levels compete for the chance to go to the National Championships. In the United States, the country is divided into three Sections-East, Midwest, and Pacific Coast-and each Section has three Regions. In the fall, skaters compete at Regionals. The top four in each Region move on to Sectionals, and the top four of each Section qualify to go on to Nationals. As you can imagine, just making it to the National Championships is a dream come true for most skaters, so there is a lot on the line at the smaller qualifying competitions. Like the non-qualifying competitions, Regionals and Sectionals are very inexpensive, so we highly recommend checking them out if you can. At these events, you get to mingle with the hard-core fans and the skaters' families.

Elite Eligible skaters (such as 2000 National Champions Michelle Kwan and Michael Weiss) are exempt from qualifying for Nationals each year, so they spend their autumns competing in a series of competitions that pit them against the best skaters in the world. This series of competitions is called the Grand Prix, and it consists of six events held in North America, Europe, and Asia. Since the top skaters in the world participate in the Grand Prix, fans see these events as an early peek into how the season will unfold.

Every skating season ends with the World Championships, which take place in March or April. "Worlds" is the only event where all the top skaters from every country meet (Grand Prix events have much smaller fields, so only 8 or 10 skaters meet up at each of those) and it is therefore seen as the worlds top competition of the year.

In addition to Non-Qualifying, Qualifying, National, World, and Grand Prix events, there are also made-for-TV competitions designed to display the top talent in the country. The formats in these events, dubbed Pro/Ams because Eligible and Ineligible skaters are allowed to compete against each other, are always in flux. Sometimes there are team events in which skaters from different countries are pitted against each other; sometimes it is boys against girls. Whatever the format, these events are seen as fun fluff and they are one way in which Eligible skaters can earn money (not to mention get that all-important TV time).

Finally, we would be remiss to neglect the top figure skating competition in the world: the Winter Olympics. Held only once every four years, every skater values an Olympic gold more than any other honor. The next Winter Olympics will be held in Vacnouver, Canada in 2010, so you should, perhaps, think about ordering tickets now. But attending such an important event ain't cheap: tickets for the preliminary rounds cost $35 - $275, and tickets for the medal rounds cost $50 - $400.

Illustrations proivided by Julie Yu Chin Liu and are 2000, SoYouWanna.net, Inc.